Fascinating to see what books manifest in Value Village in Pembroke, Ontario, which I discover is the only institution resembling a British charity shop that is to any degree widespread in this huge country. Trawling through knock-off editions of British classics – abridged Jane Austens etc. – I discover Ragged Dick and Struggling Upwards, by Horatio Alger, Jr.

The book has been written in, angrily, by some Eastern Ontarian Marxist, who connects this writer (unknown to me, at the time of trawling) to an entire doctrine. “Contrary to the Horatio Alger myth” – so the mysterious hand copies – “The Alger Hero’s improvement in station is not brought by hard work; rather, success invariably comes through the intervention of a wealthy gentleman for whom he happens to perform some act of bravery.” This is apparently found in Silvery, Children’s Books & Their Creators.

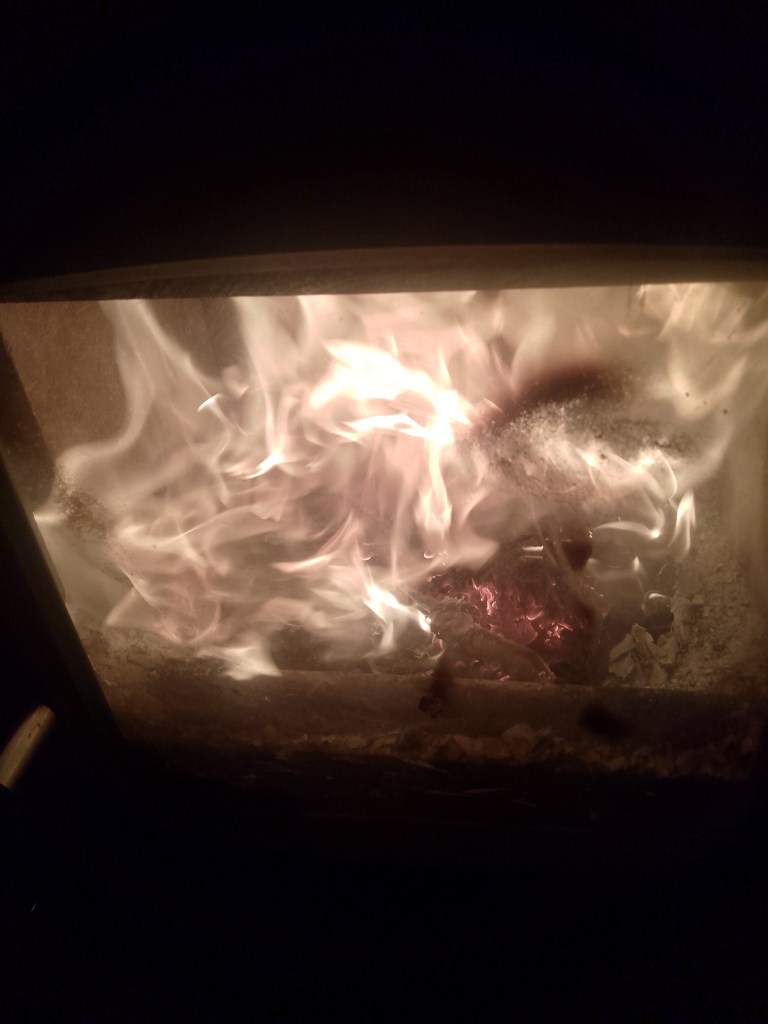

Before I do indeed burn the lamentable book on the fire, allowing it to struggle upwards in flames, I did use it as a vehicle of pondering. I have been thinking a lot about dialect; everybody speaks in some kind of dialectal way, and nobody speaks as text (if that makes any sense); even Received Pronunciation is derived from some kind of hodgepodge dialect; so why is it we have to so adamantly draw attention to certain bits of dialect, so the reader struggles as much as possible to make it out? This is apparently called “eye dialect”: as G.P. Krapp explains in the first usage, it is a “friendly nudge” to the reader, rather than a “genuine difference in pronunciation”. It is a joke, an orthographical convention alone, a reminder to the reader of the principles of genuine orthography. One of the amusing usages on OED is an inverted parody of RP, using “shiteing” to represent the way “shouting” is rendered in orthography.

In other words, “eye dialect” – I suppose an oxymoron – only makes sense in some kind of structural relationship to an author who clearly does know “how to spell”, or at least has some awareness that one is supposed to spell correctly. In Tales of Chemical Romance, by Irvine Welsh, protagonist Freddy’s attestation to a drug dealer he is “foine, me old mucker” reminds us, with “eye dialect”, we have entered squarely the realm of an anti-hero. Freddy, who works with corpses, comically objectifies the dead, and the vernacular observations underpin his not entirely intellectual-clinical attitude towards them:

Freddy ran his hand up the perfect one. It felt smooth. – Still a bit wahrm n arl, he observed, -bit too waarm for moi tastes if the truth be told

In other words, the writer is required to take an almost Stylitic position of snobbery, where dialect here communicates we are in the territory of an authentic weirdo.

Eye dialect exists in those writers who do write in “standard English”, but want to keep their hand in with the vernacular. How this functions in poetry is more complicated, since poetry is supposed to bear the closer stamp of speech. I guess it ramps up the raw speechiness of poetry? Robert Service’s Rhymes of a Red Cross Man features this technique, throughout the ironically titled “The Odyssey of ‘Erbert ‘Iggins”:

Me and Ed and a stretcher

Out on the nootral ground.

(If there’s one dead corpse, I’ll betcher

There’s a ‘undred smellin’ around.)

Me and Eddie O’Brian,

Both of the R. A. M. C.

“It’as a ‘ell of a night

For a soul to take flight,”

As Eddie remarks to me.

Me and Ed crawlin’ ‘omeward,

Thinkin’ our job is done,

When sudden and clear,

Wot do we ‘ear:

‘Owl of a wounded ‘Un.

Dialect is viscera, earthiness, in other words – it is an escape from the manacles of propriety. World War I-era poets Robert Service, David Jones, Wilfred Owen, T.S. Eliot etc. all use dialect in poems about the Great War, situating us there in the ordinariness of a couple of young lads talking, about to die. For Owen and Service this is poetry exclusively in dialect that hits us like a shell when we are consuming otherwise non-dialect poems, sonnets and the like. Mancunian dialect, for example, is employed by Owen in “The Chances”, where one of the Manchester Regiment delivers a “dramatic monologue”:

I mind us ‘ow the night before that show

Us five got talking – we was in the known

In other words, “dialect” is always self-conscious in poetry, or dialect ossifies into self-consciousness in poetry. This might be the best way of understanding even John Clare, who steadfastly holds on to his own dialect to describe the natural world, even when the dialect region he grew up in – the North Northamptonshire dialect infused environs of Helpston, Glinton, – has been altered beyond recognition; where much of what infused the dialect (dialect as circular, as recurring, as tied to an older agrarian rhythm) has been “developed”, enclosed. In “The Flight of Birds” – a poem of unimpeded movement in standard English – Clare surprises us with dialect terms:

The crow goes flopping on from wood to wood,

The wild duck wherries to the distant flood,

The starnels hurry o’er in merry crowds,

And overhead whew by like hasty clouds,

Clare knows that “starling” is the “right word”, but cannot help himself designating these starlings as our starlings, the starlings or “starnels” nested in the poem themselves. (This is not to remark on the wonderful precision of the wild duck wherries – a wherry is a light rowing boat. The movement is likened to a particular vessel, the word itself mimetic of the vessel, blah blah.)

What interested me about Ragged Dick, then, was the way in which, contrary to these positive uses of dialect, eye dialect was associated with bad education, and the character’s maturity is linked to their learning to unknot themselves from their charming native dialects. Ragged Dick is extricated from shoe shiningness with honesty and trustworthiness, and part of his journey into respectable and boring clerical work is the losing, the loosening, of the diphthongs. Dick doesn’t want to expose the contents of his “valooable pocket book” to a woman accusing him of theft, in an act of irony, seeing as he has nothing: he laments that rich people have “private tootors”. All the time, we are meant to be aware of Dick’s potential for education, even as the eye dialect becomes more steadfast in its vocabulary, maturing to “destitoot” (“I’m in destitoot circumstances”), and “loocrative perfession”. All the time eye dialect is central to the irony, of the self-madeability of the New York accented Dick.

Eventually, we see the self-editing that Heaney claimed negatively made him write “Worked” instead of “Wrought” in “Digging”, an inculcated sense of the invalidity of one’s own dialect:

Dick was about to say ‘Bully’, when he recollected himself, and answered, ‘Very much’.

Finally, Dick has learnt how to code-switch, but his retention of the dialectal Id, the voice that does initially urge him to use vernacular, is central to the self-made man’s double-nature.

Equally, as a temperance advocate, Alger connects the genteel voice that urges us to say ‘Very much’, milder than the impetus of our own dialect – apparently this occurs in Thomas Decker in 1600, “to please my bully king” – with restraint, forbearance – despite the illustrious history of the original adjective.

This might explain a little bit about US/Canadian society, more dialect spurning than British. I have been playing Scrabble obsessively recently, one of the many sins I am praying for deliverance from; in British scrabble, dialect and standard words mingle, ‘JO’ and ‘LOITERER’ are both high-scoring words for different versions, but the American is expunged of dialect. Is it part of the American psyche to connect dialect to an-education? Ee by gum, I’m not sure.

Equally, in the latter story within the Penguin edition of Ragged Dick and Struggling Upward, another story is included; “Luke Larkin’s Luck”. It is the highwaymen who harass our hero that use dialect, whose Puritan wealth-lusting virtue is embodied in his Standard English. Luke is saved by his Standard English gentility by being mild and virtuous enough to be taken pity on by the capitalists, who pay his mother to look after a child in response to deciding they like him because of such like qualities. Who save him.

Before throwing the book on the fire, (the cost of living crisis has reduced me thus), I remember what I realise now is an oddly ironic interaction with this book. I meet a little girl on a train, with her mother. With 50 minutes to kill, I proceed to try to teach the little girl how to read. I’m reading this book, and she starts writing her name on it, which I start correcting. Was I the capitalist, enforcing propriety and eye-dialect-erasure? And is the kind of equality real – the so-called Algeristic equality – that anyone at all is technically capable of advancing, with a concoction of skill and luck.

https://www.waterstones.com/book/poems-sketched-upon-the-m60/sam-hickford/9781912412334

Eye-dialect. Not the first time I saw it used, but the first time I heard the term in a critical sense, was when I studied ‘Wuthering Heights’. The cantankerous Yorkshire servant Joseph, who never had a good word to say about anything or anybody not covered by the strictest rules of the Old Testament, was one of the first notable characters in fiction to have his speech rendered as it sounded. Funnily enough, the line of dialogue I remember best was his mockery of the way someone else spoke. “Mim! mim! mim! Did iver Christian body hear aught like it? Mincing un’ munching! How can I tell whet ye say?”

As a child, my party piece was always reciting from memory one of Marriott Edgar’s Lancashire monologues – usually ‘Battle of Hastings’ or ‘The Magna Charter’, but I could also make a fair stab at ‘Albert and the Lion’ or ‘The Runcorn Ferry’.

However, when does “eye dialect” simply become writing things down the way they are now written down? Whole Wikipedia articles can be found in Scots (which some people still argue is a “dialect of English” rather than a language in its own right) for example, and Linton Kwesi Johnson’s entire corpus is rendered in Patois/Nation-Language. I wouldn’t actually call either “eye-dialect,” but there was never an Académie Écossaise or an Académie Jamaïcaine to establish just how things were to be written. In each case they are written as they would be understood or voiced by someone familiar with pronunciation in English.

It’s a comparatively modern thing. When Shakespeare wrote lines like “Now is the winter of our discontent…” and “Go, bind thou up yon dangling apricocks…” he didn’t differentiate between a king-in-waiting and a rude mechanical in the language he used. It was only later that we acted Richard of Gloucester with an RP accent and the gardener in a “Mummersetshire” accent.

Speaking of RP, I can recall someone lampooning the speech of a “Sloane Ranger” – remember them? – with the words “asseleetely heege!” (absolutely huge). I could talk about this subject all day.

LikeLiked by 1 person